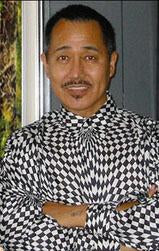

Hisashi Otsuka was born in Tokyo in 1947 into an exceptionally creative family. Schooled in Zen and the martial arts, he has lived and worked by the warrior’s code of discipline and duty. His natural artistic talents were encouraged and eventually developed formally in apprenticeship to one of Japan's foremost designers of kimonos, Taeko Jo. When Otsuka first came to Tasko Jo, he did little more than clean brushes and cook for the staff. The Bushido code, which specifies training in all the arts and sciences, determines that the technique of the art form is taught only after the student has learned service, duty and discipline. It was three years before Hisashi Otsuka could cut a piece of cloth or paint a single stroke. Otsuka remained with Taeko Jo for eight years. Like the samurai in many of his paintings on fabric, He is an artist of remarkable dedication. Rooted in Japanese tradition yet adventurous in nature, he is known throughout the world for his boldness of color and style that mark Hisashi Otsuka as truly unique.

Hisashi Otsuka’s work today is a powerful balance of ancient Eastern techniques and modern Western ideas. Like a concert musician with perfect pitch, he has perfect color memory and sense. His time-honored poets and warriors, kabuki figures, ukiyo-e women, and elegant calligraphy are steeped in the classical past. Yet in color and composition, his work achieves a vigorous, contemporary context. Monumental in scope and meticulous in detail, it offers a total aesthetic of heroic and subtle impact at once. In addition to rigorous self-discipline and dedication, Bushido training also encourages fierce independence and aesthetic sensitivity. For Otsuka these last two requirements clashed with the most basic tenants of Japanese aesthetics, that contemporary arts seek the perfection of traditional forms, that they retrace the inspirations of the old masters and not embellish classical accomplishments. Enormous social and spiritual pressures compel today's Japanese artist to conform to the designs, styles and colors of the past. Otsuka found this pressure stifling. His own aesthetic, more inventive, sought to design new compositions, in larger works, with brighter colors. Inevitably his work communicated the vitality, the dynamic excitement, of his own soul.

Hisashi Otsuka came to the West, to Hawaii, in 1979. Until that time his painting had been historical in subject and theme. Otsuka brought to the West all the gifts Japan and its culture can bestow on an artist, in return, the West gave him the opportunity to express himself freely and rewarded his expression by its "grateful acceptance" of his work, as witnessed by the large and growing number of his collectors. The Western world has good reason to be grateful. Except to those few who have a special affinity for Japanese cultural values, or who have trained themselves to appreciate them, the understated colors and static forms of Japanese art have always seemed remote and unexciting to western collectors. The West has traditionally required, for excellence in art of whatever form, some element of uniqueness, of individuality and originality. The art which excites us most is art that unsettles us, that, by a new approach, a different perspective, an unusual arrangement of forms or ideas or symbols, a bold expressive use of color, startles us into some new perception or insight. Otsuka does this. Most westerners know the traditional designs, colors, styles, and forms of classic ukiyo-e. Few art lovers in the West are moved by them, but in the artwork of Otsuka we find them in large compositions with unusual kimono designs, flowing hair, bright colors, movement and grace.

Hisashi Otsuka's newest contemporary art deco works are turning or returning to Oriental themes and exploring modern concerns. East Meets West and Harmony comment explicitly on the significance to the modern Oriental woman of the traditions and values of the past. They suggest that Hisashi Otsuka, having burst through his own aesthetic frontier and claimed his own artistic freedom in Sisters, is now no longer threatened by the conventions of his past and his classical training. Now he can acknowledge them and, like Lady Mieko, celebrate their significance: the artist he is today could not exist without the values and traditions of his past. These new works seem to be Otsuka's attempt to forge a new artistic reality, one that insists on the value of the past even while it focuses more precisely on contemporary realities, one that applauds the freedom possible in the West even while it seeks more carefully to balance Western and Eastern themes and points of view.

Hisashi Otsuka's individual and unique paintings move us gradually and inevitably to a greater appreciation and understanding of the older forms and cultural values of Japan This, after all, is Otsuka’s personal mission, and he pursues it with splendid dedication. In New York, London, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, and Hawaii, Otsuka’s one-man shows have earned the highest praise. His international prominence increases year by year, making him truly a dominant force on the world art scene. To Otsuka, life and art create each other. He, the master, the warrior, devotes himself to the fabric of both, wielding his brush like a sword.

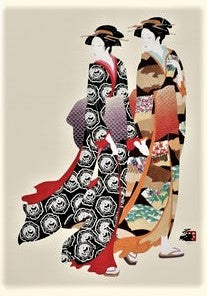

Vendor:Ukiyo-e Sisters - Limited Edition Printers Proof Lithograph on Paper by Hisashi OtsukaArt Deals

Vendor:Ukiyo-e Sisters - Limited Edition Printers Proof Lithograph on Paper by Hisashi OtsukaArt Deals